St Neots during the Civil

War

Source A:

The quarrels between king

and parliament culminated inevitably in the Civil War which began in 1642.

Loyalties were divided locally and there was support for both sides. Sir Edward

Montague, Earl of Manchester, supported Parliament and became an important

officer in the Roundhead Army, but his uncle, who was lord of the manor of St

Neots, was a Royalist who had several times entertained the king at

Hinchingbrooke and he supported Charles. Sir James Beverley of Eaton Socon was

for Parliament but the Gery family of Bushmead were Royalists. William Gery

fought in the Royalist Army and was taken prisoner at the surrender of

Colchester in 1648 and his brother George was captured at (The Battle of) Naseby

in 1646. The sums of money required to ransom them severely depleted the value

of Bushmead estate.

The ordinary townspeople

and villagers of the local area probably differed in their loyalties too, but

if there were supporters of the king at St Neots they would have kept their

opinions to themselves during the early years of the war as there were

Roundhead soldiers in the town for several months. In 1643 some of the troops

commanded by Sir Edward Montague were ‘guarding St Needs’ and evidently fearing

attacks from the king’s forces from across the river, because part of the

bridge had been converted into a drawbridge to prevent access from the west.

Although many people in

Huntingdonshire supported Oliver Cromwell because he was the local member of Parliament and a dominant figure in the

Parliamentary Army, there were many others who did not. When the king travelled

from Huntingdon ‘unto St Eotes’ on his way to Woburn in 1645 he gathered

several hundred recruits to his cause en route, making his force so strong that

a troop of Roundheads who were following after him were discouraged and

retreated.

(Young, R. (1996), 'St

Neots Past', Phillimore, p.53 )

- Who wrote this

evidence and when (author and date)?

- Where does this

evidence come from (Title and page numbers)?

- Who published it?

- Is it primary or

secondary evidence?

- Is it useful and why?

- Historians ought be unbiased. What evidence is there that the

author favours the Royalists, the Roundheads or is impartial?

- Some text (not in

italics) has been added in brackets that was not

in the original document. Why?

- Which local

landowners supported King Charles and which supported Parliament?

- Why did the value of

Bushmead estate drop in value after 1646?

- Why do you think

local townspeople kept their opinions to themselves during the early years

of the war?

- What defensive work

did Sir Edward Montague’s troops do and why?

- What were the two

names used for St Neots during the Civil War?

- Why did the Roundheads who were following King Charles’s forces in

1645 retreat?

Source B: The

‘Battle’ of St Neots

St Neots was spared a battle on that occasion but

three years later, in 1648, it was the scene of a

skirmish which merited the publication of a special pamphlet to describe it. A party of about one hundred Royalist cavalry under Henry Rich,

Earl of Holland, having suffered defeat in a battle at Kingston-upon-Thames,

retreated northwards. On their way they were joined by several more

officers and soldiers, including the Duke of Buckingham, the earl of

Peterborough and a Dutchman, Colonel Dolbier.

They arrived in St Neots late one night, (Sunday, 9th

July, 1648) by then some 300 strong, and the Earl of Holland, assured the

townspeople that they intended no harm but simply required somewhere to rest

for the night. The soldiers made camp on the Market Square leaving a small

party to guard the bridge, and the officers retired to various inns to sleep.

The largest local inn at the time was The Cross Keys and it is likely that the

earl of Holland would have taken a room there. The Duke of Buckingham did not

stay in the town but went to ‘a gentleman’s house’ a few miles away, perhaps

Paxton Hall at Little Paxton.

Early the following morning a troop of about one

hundred Roundhead soldiers arrived, led by Colonel Scroop, having pursued the

Royalists from Kingston. They easily overcame the party of men guarding the

bridge and advanced into St Neots to attack the troops on the square. The

Royalists, although they outnumbered their assailants, were caught unprepared

and had no time to engage in the lengthy process of loading their muskets, so

they had to fight with swords. Being still drowsy from sleep they were no match

for the Parliamentarians and the battle was short and sharp. They were few

fatal casualties, only four officers and eight Royalists being killed, with the

Roundheads losing only four men. The Royalists, including most of the other

officers, were then taken prisoner. The Earl of Holland, roused from his bed at

the inn, was reputedly so unprepared that he did not have time to dress

properly and he was taken prisoner in his undergarments! The Duke of

Buckingham, who had arrived late on the scene from his out-of-town location,

escaped with about one hundred soldiers and was able to make his way to France,

but the earl of Peterborough, who also fled from the battle, was captured

later.

The jubilant Roundheads marched their prisoners

down St Neots High Street and locked them in the parish church (St Mary’s) They were later taken to Hitchin but what became of them is

unknown. The Earl of Holland was sent to Warwick Castle to be held and the

following year was tried and executed.

The pamphlet which was published to celebrate the

battle of St Neots listed a number of items which were taken by the victors and

they included 200 horses, 150 firearms, ‘silver and gold and store of other

good plunder’, and the earl of Holland’s Order of St George’s medallion on its

‘blew ribbon’. As well as the military personnel who were captured there were a

number of civilian servants, including the Earl’s personal surgeon.

(Young, R. (1996), 'St

Neots Past', Phillimore, pp.53 – 54)

14

Who were the main Royalists who stayed in St Neots in 1648?

15

Which other local ‘gentleman’s house could the Duke of Buckingham have

stayed at in 1648?

16

How many Roundheads were following them and who was their leader?

17

How many people were killed in the ‘Battle’ of St Neots?

18

How many survived and why do you think they managed to escape?

19

What happened to the prisoners?

20

What was captured?

21

What do you think ‘other good plunder’ was?

22

Historians ought be unbiased. Is their any hint

that the author favours the Royalists, the Roundheads or is impartial?

23

Some text (not in italics) has been added in brackets

that was not in the original document. Why?

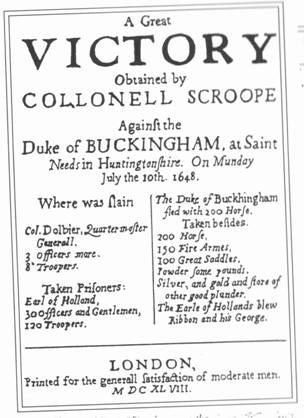

Source

C:

The front cover of a

pamphlet describing the battle of St Neots in 1648

24 Is this primary or secondary evidence?

25 Who do you think published it and why?

26 Why is it a useful source of evidence?

27 What additional information does it provide that

Source B does not give?

28 What are the Roman numerals for 1648?

29 Describe the strength of the Royalist army.

Local legend has it that troops were stationed in

St Neots Rectory during the Civil War and that the soldiers who took the

prisoners into St Mary’s church then fired their muskets into the air. Scroop

and two other names are inscribed in lead on the nave roof with the date 1674.

Some historians use this evidence to suggest that the Colonel made a

contribution to help replace the lead after the incident.

It

is said that St Neots Rectory is haunted. Noises were heard at night and some

claimed to have seen Civil War soldiers walking in the rooms.

Several

roads in the town are named after people and events in the Civil War, e.g.

Cromwell Road,

See

if you can find out any others? (clue: Battles,

military leaders)

Source D - Extract from St Neots

Town website

The Civil War

Playing its part in the Civil

War, sections of the bridge were dismantled and drawbridges inserted to impede

the Kings progress. Similar alterations were made to the bridges of St Ives and

Huntingdon.

July 9th 1648 a battle

between the forces of the Civil war took place at St Neots. The resident

parliamentary forces beat off the Duke of Buckingham and the Earl of Holland.

Buckingham escaped as far as Houghton, a village on the river Ouse. The Earl of

Holland was captured and executed despite the recognised terms of surrender

then in place, a scandal of the time.

http://www.stneots-town.info/town/info/history/civil_war.htm

Source E - Extract from St Albans

website - A

Civil War Miscellany

Author: Alf Thompson, The Earl of Northampton’s Regiment : Orders of the day, Volume 31, Issue 4, 1999

In July 1648 The Earl of Holland and the young Duke of Buckingham, having raised 1,000 horse, attempted to support the main Royalist Army by attacking Fairfax from the rear, but were cut off and defeated at Kingston. Holland retreated with some 500 men to St Albans where he unsuccessfully tried to rally support. With the Parliamentarian army hot on his heels he withdrew to St Neots; having underestimated the closeness of his assailants he quartered for the night. The Parliamentarians surprised him during the night and gave battle. Holland was easily defeated, arrested and later tried and executed. The Earl of Holland and the Duke of Hamilton were executed on the same day as Arthur Lord Capel, the ardent Hertfordshire Royalist. Cromwell advised Parliament to put Capel on trial rather than deport him, because he recognised that he would always be constant to the Royalist cause.

http://www.sealedknot.org/knowbase/docs/0046_StAlbans.htm

Source

F - Extract from Wikipedia’s entry on the Duke of Buckingham

George

Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Lord Francis was killed near

Kingston, and Buckingham and Holland were

surprised at St.

Neots on the 10th, the duke succeeding in escaping to the Netherlands.

In consequence of his participation in the rebellion, his lands, which had been

restored to him in 1647 on account of his youth, were again confiscated, much

of them passing into the possession of Thomas Fairfax; and he

refused to compound. Charles II conferred on him the Order of the

Garter on September 19, 1649, and admitted him

to the Privy Council on April 6, 1650.

http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Villiers,_2nd_Duke_of_Buckingham

![]()

Source G – Extract from The

History of Hinchingbrooke House website

|

The

History of |

|

|

|

Hinchingbrooke

House |

|

Hinchingbrooke was sold to Sir Sidney Montagu on 20 June 1627.

Sir Sydney was married to Paulina, daughter of John Pepys of Cottenham,

great Aunt to Samuel

Pepys. Their eldest son had drowned in the moat at Barnwell, which

partly explains their move to Hinchingbrooke House. Sir Sydney’s brother Edward was the first Lord Montague of Boughton

Northamptonshire, and his other brother Henry was first Earl of Manchester

with his seat at Kimbolton Castle. The Montagues were an influential and powerful

family.Sir Sidney Montagu was one of the Masters of Requests to Charles I

and an ardent supporter of the royalist side in the Civil War.

He died in 1644 and the estate passed to his son Edward Montagu, who carried out significant building works on Hinchingbrooke House.

Edward Montagu, fought on the Parliamentarian side during the first Civil War. Charles I slept at Hinchingbrooke in 1647 as a prisoner on his way from Holmby House to Newmarket. He was the prisoner of the radical Parliamentarian Cornet Joyce while Edward's wife Jemima entertained the king "magnificently and dutifully".

Despite fighting against the Royalists as a Colonel in

Cromwell's army in the first Civil War Edward Montagu took no part in

the second civil war and helped the restoration of Charles II to the throne -

even collecting Charles from France when he made his return to England.

On 12 July 1660 Edward was given the title Baron Montagu of St. Neots, Viscount

Hinchinbrooke and Earl of Sandwich.

![]()

http://www.hinchbk.cambs.sch.uk/historical/hinchhistory/edward/edward.html

Source H - Extract from St Neots Town Council website.

History of the Town - Oliver Cromwell

It is difficult to imagine the devastating effect of Civil War, but in 1642 England was to be embroiled in such a bloody war. Families and friends split apart by dividing loyalties. The outcome was to result in the execution of Charles I and this country for the first and only time a Republic under the leadership of the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. Of this great man little need be written, but history frequently maligns this "man from Huntingdon".

He was a born leader, capable and fair-minded. He went to great lengths to avoid the execution of the King - the rest, as they say, is "history", but it is due to this man alone that we enjoy the privilege of our present democracy. St Neots was, of course, in the heart of Cromwell country and in general supported his cause, although it was said that the town had rather more Royalist sympathy than most in Huntingdonshire.

In 1648 a short but decisive battle occurred in St Neots when a party of Royalists, led by the Earl of Holland and other high ranking officers, including the Duke of Buckingham and the Earl of Peterborough, entered the town, taking it in the Kings name. During the early hours of July 10, having retired for the night, the Earl of Holland in the Cross Keys Hotel, was unexpectedly attacked by a force of Parliament's Army under command of Cromwell's famous Colonel Adrian Scrope, and there followed a short but heated battle at the foot of the Bridge and on the Market Square, which resulted in victory for Colonel Scrope and total defeat for the Royalist Party.

Although this battle was of short duration, Parliament was much elated at the outcome and to celebrate the event declared July 19 a day of Public Holiday and Thanksgiving throughout the country. The unfortunate Earl of Holland was sent to trial, found guilty of treason and executed on March 9 the following year, before Westminster Hall, just a few weeks after the execution of Charles I.

http://www.sntc.co.uk/history.htm

Source

I -Extract from Wikipedia’s entry on the Earl of Holland

Earl

of Holland

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

On Sunday, July 9, 1648, seven months

prior to the execution of King Charles I of England, Henry Rich, 1st

Earl of Holland, and his army of approximately 400 men entered St

Neots in the county of Huntingdonshire.

Rich was baptized on August 19,

1590 and he was

probably born earlier on the same year. He was the son of Robert

Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick and of Penelope Rich, and

the younger brother of John Rich,

2nd Earl of Warwick. He began his career as a courtier and soldier

in 1610, swiftly

becoming a favourite of King James I of England, but fell out of favour on

the accession of Charles I.

The Earl's men were hungry

and weary, following their escape from Kingston-on-Thames,

where the Parliamentary forces had completely overwhelmed them. Of his original

army of 500, the Earl escaped with around 100 horsemen and were

immediately followed by a small party of Puritan and Parliamentary horsemen.

After much hesitation regarding in which direction they should flee, the Earl

decided on Northampton, and the group made their way via St Albans

and Dunstable.

Upon the outskirts of Bedford the group turned eastward towards St Neots town.

En route from Kingston, the Earl was joined by the young George Villiers, 2nd Duke of

Buckingham and the Earl of Peterborough.

Colonel Dolbier,

an experienced soldier and Dutch national, had also joined them. The Roundheads

hated Dolbier, as he had previously served with them under the 3rd Earl

of Essex until taking up arms in favour of the Royalist cause.

The filed officers of

Holland’s force sought only rest and safety. Colonel Dolbier called a council

of war, where many officers voted for dispersing into the surrounding

countryside. Others suggested they should continue northwards. Colonel Dolbier

advised on the strategic position of St Neots and the fact that the joint

remnants of Buckingham and Holland’s forces had increased sufficiently since

the retreat from the Roundheads at Kingston. He suggested they meet and engage

their pursuers. He further added that, by obtaining a victory, the fortunes of

war could be turned in their favour. Due to his vast experience as a soldier,

his words were listened to with respect. He further offered to guard them

through the night in case of a surprise attack, or meet the death of a soldier

in the defence of the town. A vote was taken and Dolbier’s plan was adopted.

The Earl of Holland who, it

was said, “had better faculty at public address than he had with a sword,”

joined the Duke of Buckingham and the Earl of Peterborough in addressing the

principal residents and townsfolk of St Neots. Buckingham

spoke at length, claiming “they did not wish to continue a bloody war, but

wanted only a settled government under Royal King Charles.” Assurances were

also given that their Royalist troop would not riot or damage the townfolks’

property. Of the latter, it is recorded that they were faithful to their

promise.

Fatigued by their battle and

consequent retreat from Kingston, the field officers eagerly sought rest.

Colonel Dolbier, true to his word, kept watch over them.

The small group of Puritan

horsemen who had pursued them had, upon reaching Hertford, met with Colonel Scroope

and his Roundhead troops from their detachment at Colchester.

At 2 o’clock on Monday

morning, July

10, one hundred Dragoons from the Parliament forces arrived ahead of the

main army at Eaton Ford. Colonel Dolbier was at once informed, and immediately

gave the alarm: “To horse, to horse!”

The Dragoons, equipped with

musket and sword, crossed St Neots’ bridge before the Royalists were fully

prepared. The battle of St Neots had begun.

The few Royalists guarding

the bridge quickly fell back from the superior numbers before them. The ensuing

battle was now fought on the main square and streets of the town. The remaining

Royalists were now fully prepared for combat. The main army of Roundheads had

also arrived, and a further wave of Puritans crossed the bridge into town. The

battle was fierce, with the Puritans gaining ground.

Colonel Dolbier died during

the early stages of the battle. Other Royalist officers, including Colonel Leg and Colonel Digby,

were also killed during the battle. Other officers and men drowned whilst

attempting to escape by crossing the River Ouse.

The young Duke of Buckingham, being overwhelmed by the speed of these events,

escaped to Huntingdon with sixty horsemen, with the intention of continuing

towards Lincolnshire. Upon realising the Roundheads were in hot

pursuit, he changed plans, and via an evasive route returned to London from

where he later escaped to France.

The Earl of Holland with his

personal guard fought their way to the Inn at which he had stayed the previous

night. The gates had been closed and locked, but were quickly opened to admit

him. Although the gates were immediately closed again as he entered. The

Parliamentarians soon battered them down and entered the Inn. The door of the

Earl’s room was burst open to reveal him facing them, sword in hand. It is

recorded that he offered surrender of himself, his army and the town of St

Neots, on condition that his life was spared.

The Puritans seized the Earl

and took him before Colonel Scroope, who ordered him to be shackled and

imprisoned under guard. The remaining Royalist prisoners were locked in St

Neots parish church overnight, then taken to Hitchin

the following morning. The Earl and five other field officers were taken to Warwick

Castle, which had remained a parliamentary stronghold throughout the war.

They remained prisoners for the next six months, until their trial for high

treason. In London it was said “His Lordship may spend time as well as he can

and have leisure to repent his juvenile folly.”

The Earl of Peterborough

also escaped dressed as a gentleman merchant, but was later recognised and

arrested. Friends aided their escape again whilst en route to London for trial.

He then stayed at various safe houses, financed by his mother, until he managed

to flee the country.

On February

27, 1649 the

Earl of Holland was moved to London for trial. He pleaded his crime was not

capital, and claimed that he had surrendered St Neots town on the condition

that his life would be spared.

It was stated at the time that

in 1643 Earl of Holland had joined Parliament and in the same year had changed

sides and joined the Royalists. He was with the King at the Battle of Chalgrove

– Oxford – but stole away during a dark night before the close of battle. On March 3 the

Earl was condemned as a traitor and was sentenced to death.

His brother, the Earl of

Warwick, and the Countess of Warwick petitioned Parliament for his life, as did

other ladies of rank. The Puritan Parliament divided its vote equally. The

speaker gave the casting vote for the sentence to stand. The petition had

succeeded only in deferring the execution for two days. The Earl was

dangerously ill during these days and neither ate nor slept.

On the morning of his

execution on March

9, before Westminster Hall,

the Earl walked unaided, but spoke to people along the way, declaring his

surrender at St Neots was on condition that his life would be spared. At the scaffold

he prayed. He then gave his forgiveness to the executioner and gave him what

money he still had on his person, which was approximately ten pounds. Upon

laying his head on the block, he signalled the executioner by stretching his

arms outwards.

His head was severed by one

stroke of the executioner’s axe. Very little blood flowed, due to his weakness,

and the strong feeling was that, even had the execution not taken place, he

probably would not have lived for long.

The second rising of the English

Civil War had culminated in the Battle

of Preston during August 1648, with the Roundheads marching two hundred and

fifty miles in twenty six days through foul weather and conditions, to defeat

and ensure the Royalists would never reform as an army.

The townspeople of St Neots, who

apparently were neutral during the entire conflict, continued their peaceful

existence.

http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earl_of_Holland

30. Which websites are the most useful and

why?

31. Which websites are the least useful and

why?

32. Which websites do you think provides

the most reliable evidence and why?

33. Is there any evidence that any of the

websites are biased in favour of the Royalists or the Parliamentarians or are

they all impartial?

Extension

All this information is available on the

computer network. You can access it via the Subjects, History and Get Work

folders.

Copy the text and graphics from sources A,

B and C to produce a booklet on the Civil War in St Neots.

Use any evidence

you can find in sources D, E, F, G, H and I to edit in more details to your

story.